The Center for Interfaith Relations is exploring the written works of theologians, poets and other wisdom-keepers in search of insight and inspiration. Our hope is that these written words will spur meaningful reflection and serve as a beacon of hope amid challenging times.

Cultivating Seeds of Hope and Love in the 21st Century:

My Personal Ruminations on Thomas Merton

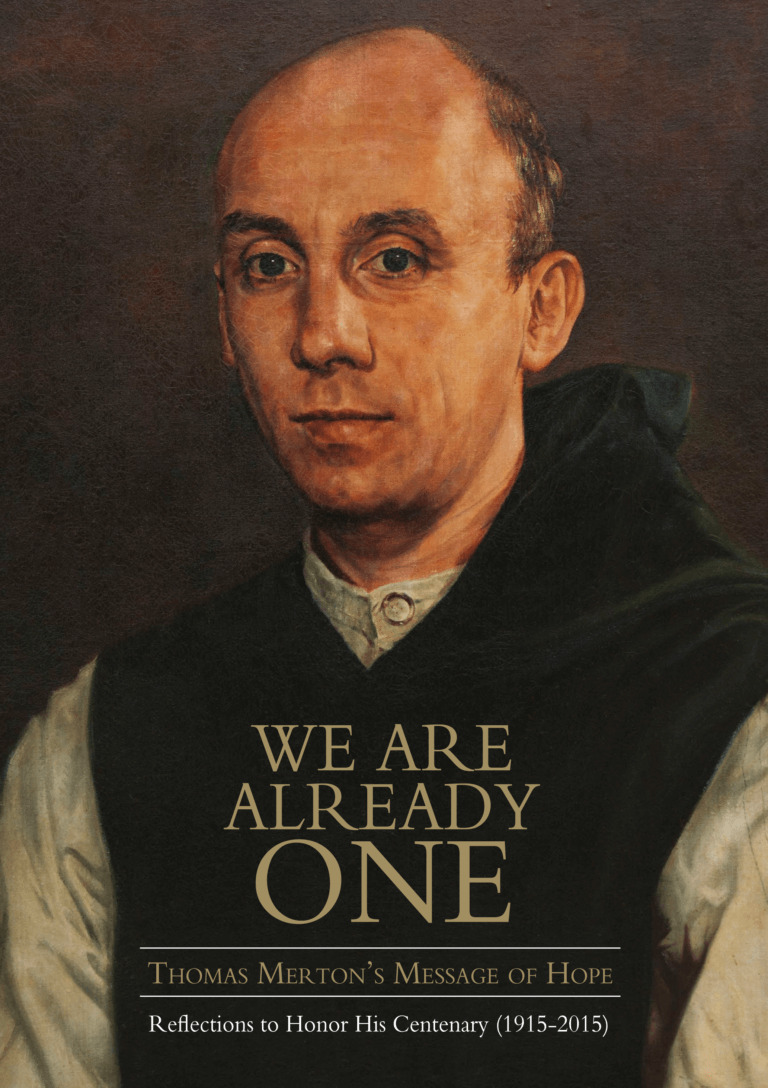

By Cristobal Serran-Pagan y Fuentes | From the Collection “We Are Already One“

Thomas Merton is one of my spiritual heroes. My first encounter with Merton’s writing was as an undergraduate student at St. Thomas University (Miami, Florida). I took an honor’s class where we read Merton’s autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain. Later on as a graduate student I went to Boston College and Boston University where I fell madly in love with studying mystics from all cultures and religious traditions.

Thomas Merton is one of my spiritual heroes. My first encounter with Merton’s writing was as an undergraduate student at St. Thomas University (Miami, Florida). I took an honor’s class where we read Merton’s autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain. Later on as a graduate student I went to Boston College and Boston University where I fell madly in love with studying mystics from all cultures and religious traditions.

Every day when I wake up I begin my ritual honoring the great spirits of St. Teresa of Avila, St. John of the Cross, Mohandas K. Gandhi, Teilhard de Chardin, Martin Luther King, Jr, Thomas Merton, Howard Thurman, Dorothy Day, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Thich Nhat Hanh, and His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama. All these leaders share in common a deep love for humanity that transcends cultural and religious boundaries.

Merton’s spiritual legacy has left a profound effect on my whole being. I am fascinated by the mystical theology of hope and love in his life and writings. The Trappist monk invites each one of us to become full partakers in building the kingdom of heaven on earth. Merton’s contemplative-prophetic message is even more urgent for us today because we are in the midst of great social, political, ecological, spiritual, and religious turmoil.

Genuine mystics are able to integrate a contemplative desire for the glory and love of God with an apostolic and social commitment for their neighbor as well as for all creation. The prophetic voice demands witness and response to the most pressing religious and moral issues of our time. True contemplatives stand up as prophetic witnesses to justice and peace in their unique ways, asking for forgiveness and reconciliation in times of crisis. True mystics do not turn their backs to the suffering inflicted on millions of people in different parts of the world. They do not withdraw completely from society in search for solitude. Instead, they protest against the individual and structural evils of their respective societies. Their spirituality is based on the ideal of building a compassionate world where peace, justice and love reign, which includes the act even of loving one’s enemy.

The goal of the Christian mystic is to become God by participation so that the contemplative can share the fruits of his or her mystical vision with others by becoming a messenger of God on earth. In the Christian mystical tradition, the contemplative and the prophetic are two aspects of the same reality. Mary often symbolizes the contemplative mystic, while Martha best represents the active mystic. They complement each other. Together they symbolize the mixed life by combining action and contemplation respectively. Clearly, Merton follows this mystical tradition of contemplatives in action.

In 1958, Merton reported having a mystical vision at the corner of Fourth and Walnut Streets (today named as Muhammad Ali Boulevard) in the business and commercial district in Louisville, Kentucky. This experience narrated in Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander marks Merton’s transition from a life solely dedicated to prayer and contemplation to a life more engage with the world. After this, Merton began addressing social issuers more directly, and started to publicly denounce the Cold Ware in his letters and writings.

Merton saw the divine reflected in all things and developed a sense of cosmic interconnectedness. The epiphany that took place in Louisville has its spiritual roots in his personal encounter with the source of life. Out of this contemplative experience he gains a new perspective on life. Merton is able to reach out to the world compassionately and, in doing so, he no longer ignores the moral responsibility to both the stranger and the neighbor.

In his final year, Merton describes his own mystical experiences in his journals. Perhaps the most famous account is when he writes about his visit to Polonnaruwa. He said that he could not write adequately what he felt while he was contemplating the giant statues of the Buddha at Polonnaruwa. Merton experienced peace in its fullness, resting in complete silence before the extraordinary faces of the Buddhas. There was a sense of gratitude and awe.

On December 10, 1968, Merton received an electric shock from a faulty fan after coming out from his bath. He was in Bangkok, Thailand, attending a monastic conference. Merton the peacemaker lost his life in his beloved Asia after denouncing on numerous occasions the American participation in Vietnam. Ironically, Merton’s body was transported home to North America from an Air Force Base along with the dead bodies of American soldiers who were killed in Vietnam.

Merton thought that the root of war and unnecessary violence is fear of others who are not like us or do not think like us. The antidote for this fear is to cultivate a spiritual practice of love in action, which is based on mutual trust. Again, Merton’s personal conviction has its origins in his own contemplative vision of love’s transformative power, which led him to keep his high hopes ion humanity intact. Merton believed that the only through compassionate love that we can treat the other as one of us, because God is love. Each one of us is a reflection of God’s love, even if we are not fully aware of it. Furthermore, Merton extended his arms not only to the oppressed but also to the oppressor. And yet, Merton did not remain neutral. He took sides with those who suffer.

Merton became a witness to the truth that God is against all forms of injustice in the world; that unnecessary suffering and moral evil is a question that affects all humans because we have the capacity to choose evil, and therefore it is our responsibility to avoid evil; and finally, that God is calling humans to participate as co-creators in building the heavenly kingdom on earth by denouncing the deepest troubles of humanity and announcing the good news of a new reality, a new order that will definitely put a stop to the affliction and unnecessary suffering of the anawim, or the marginalized ones.

Merton was well aware of the need for the monk to reach out to those who suffer in this world. Merton’s contemplative message stressed the practice of love in our daily lives. However, Merton did not define this Christian love as being “sentimental.” In fact, Merton suggested that a theology of love cannot be authentic if it serves the interests of the rich and powerful to the detriment of the anawim. Indeed, Merton recognized the danger of escapism, especially in monastic circles. He warned his religious brothers and sisters not to remain indifferent to the social and religious problems of their fellow human beings. Merton clearly spoke out his mind as a mystical prophet by fulfilling his contemplative vision in the world.

Children of the twenty-first century are witnessing similar fears to those of Merton’s age. On the one hand, we are facing the fears of personal of insecurities such as conditions of poverty, of unemployment, of misfortune, of domestic violence, of lack of success, or of social acceptance. On the other hand, the global fears of terrorism, of unjust wars, of fundamentalisms, of illegal immigrants, of ecological tragedies, are the signs of our times.

The people of the world are desperately crying out for signs of hope. They are longing for new leaders who can address the social, economic and spiritual needs of the world in humane ways. Many of us wonder what our leaders are saying and doing in the midst of massive turmoil. I believe the contemplative message of Merton can help us identify the root of our contemporary problems by asking the right questions. This deep questioning in search for solutions will require from us a creative response that can directly and effectively address the most urgent problems of our time.

The Trappist monk has become a beacon of hope for humanity because he never gave up in his search for truth, peace, justice, and love. Merton devoted his life to the pursuit of building a more just and humane society where each sentient and non-sentient being is respected and valued. Merton understood the unique role each being plays in the unfolding drama of the universe. For him, a true mystic is one who actively engages and participates in the social and spiritual struggles of his or her time.

I am thankful to Merton for having planted the seeds of hope and love in his own days. His contemplative message is universal in scope. The Trappist monk brought us a prophetic message of real and everlasting peace, justice and love. His impact in today’s world resonates even louder since the most of his writings are available to us now. The major task ahead of us today is to reinterpret Merton’s own words using a contemporary language that speaks to new generations. I see myself as one of those Mertonian scholars who have taken seriously the great responsibility of passing the torch to younger generations so that we can all become real agents of love in action.